Problems

of Bovine Pregnancy

303-305,

400-401

Elective termination of pregnancy:

- The indications for elective termination of pregnancy include:

- Inadvertent breeding, such as breeding to the wrong bull, a heifer

that was too small when bred, and feedlot heifers;

- Pathologic

pregnancies such as hydrallantois.

- It should be remembered when

trying to abort feedlot heifers that if they are receiving a

progestin type growth promotant that administration should be

stopped while trying to abort them to prevent the CL

"rescue" phenomenon.

- Physical methods to terminate pregnancy include rupture of

amniotic vesicle before 65 d of gestation.

- The fetal membranes may

remain in utero for 2-3 wks after AV rupture.

- Decapitation of fetus

may be performed, usually between 65 to 90 days. It becomes

difficult after 3 mo.

- Abortion will occur in 10-14 d, the fetus may

mummify.

- Intrauterine infusions can result in pregnancy loss.

-

Enucleation of CL, although practiced in the past, is NOT

RECOMMENDED. It may result in hemorrhage (sometimes fatal) and

adhesions. It was used before PGF became available.

- Hormonal methods of

pregnancy termination

- More common than physical methods.

- During normal pregnancy, the CL is required

for the first 5 month and the last month of gestation. An extra-gonadal

source (placenta) (plus adrenals?) is available during the remainder

of gestation.

- To terminate pregnancy during the first 5 mo use PGF,

during the 6th, 7th and 8th month use PGF plus a corticosteroid

(usually dexamethasone).

- If PGF is used alone, there is sometimes

incomplete luteolysis and placental progesterone production may

rescue the pregnancy.

- Corticosteroid alone although it reduces

placental secretion of progesterone, does not cause luteolysis until

the last month of gestation. The fetoplacental unit must be mature

in order for corticosteroids to terminate pregnancy.

- During the last

month, either PGF or corticosteroid is usually sufficient.

- Estrogens

were used before PGF was available but in general have poor

efficacy. Estrogens are more reliable in the first 5 months, but PGF is

more so.

Induction of parturition:

- There are a number of indications for induction of parturition.

These include:

- 1)health of the cow - either to save her or to save

the calf because of the dam's deteriorating condition;

- 2)prevent

dystocia? - induction of parturition has been proposed as a means of

reducing dystocia because the calf gains up to 1.0 kg/d near the end

of gestation;

- 3)in dairy cattle parturition may be induced to

prevent excessive udder edema from damaging the udder supports;

- 4)in

beef cattle induction of parturition can be used to truncate the

calving season, thereby allowing more time postpartum to resume

cyclicity before the next breeding season;

- 5)management

considerations, e.g. more efficient use of facilities and manpower;

-

6)seasonal calving to allow better use of available feeds (more

common in New Zealand);

- 7)allow closer supervision to be able to

provide assistance at the earliest indication (especially with

valuable animals such as embryo transfer calves).

- There are important criteria to be met for a method to be

considered successful. A method should:

- 1)be efficacious,

- 2)provide

a predictable time of delivery,

- 3)have no adverse effects on the

health of the dam,

- 4)have no adverse effects on the health of the

offspring,

- 5)alter neither the quantity nor quality of colostrum,

-

6)not affect postpartum involution or subsequent fertility,

- 7)not

increase the incidence of retained placenta.

- Some precautions should

be considered for a successful outcome.

- You should have a fairly

accurate and reliable breeding date because while calves born up to

2 wks early have normal vigor, those born more than 2 wks premature

have reduced viability.

- If a large number of animals is to be

induced, consider the needs of a large number of calves and

husbandry requirements.

Methods used to induce parturition in cattle:

- Long acting corticosteroids are insoluble esters or

suspensions such as:

- Dexamethasone trimethylacetate (20 mg),

-

Triamcinolone acetonide (10 mg),

- Flumethasone suspension (10 mg),

-

Betamethasone suspension (20 mg).

- These are injected i.m.,

approximately 1 mo. prior to the due date.

- Parturition occurs in

4-26 d. This wide range is a disadvantage in some respects.

-

Preexisting health conditions in the dam may be exacerbated because

of the long acting corticosteroids.

- The incidence of retained fetal

membranes is low (9-22%) compared to other methods of induction.

- However, there is a high incidence of calf mortality (17-45%).

- Calf

mortality is due to premature placental separation and uterine

inertia.

- The calves die in utero and are born partially autolysed

with the membranes intact.

- Hypogammaglobulinemia is frequent in

calves born alive. This is because colostral immunoglobulins are

reduced and in addition the calves are often weak and ingest

inadequate amounts of colostrum.

- Short acting corticosteroids are soluble esters such as:

-

Dexamethasone (20-30 mg),

- Flumethasone (8-10 mg),

- Betamethasone

(30 mg).

- They are generally efficacious (80-100%).

- They can be

injected i.m. within 2 wks of the due date.

- Parturition usually

occurs in 24 to 72 h, with an average of 48 h.

- There is no increase

in calf mortality if used within 2 wks of term. Earlier than this

there is the risk of inducing a premature calf.

- Colostral

immunoglobulins are normal.

- The major disadvantage is an increased

incidence of retained fetal membranes.

- The likelihood of retained

fetal membranes is related to the degree of prematurity and ranges

from 30 to 100%.

- The earlier parturition is induced, the higher the

percent of retained fetal membranes.

Prostaglandins :

- Drugs available at this time in the US include:

- Prostaglandin F2a

(25 mg),

- Cloprostenol ( 500 ug),

- Fenprostalene (1 mg).

- They are

similar to short acting corticosteroids as far as efficacy, time

from administration to expected calving, incidence of retained

placentas, etc.

- They have no great advantage over corticosteroids.

Estrogens:

- These are generally considered an "old" method, used

before prostaglandins were available. They have relatively poor

efficacy (60-80%). They also have a high incidence of retained

placentas.

- Combinations:

- Combining short acting corticosteroids and estrogens does not

decrease the incidence of retained fetal membranes. Large doses of

estrogens decreases the interval to parturition by several hours and

reduces induction failures.

- If long acting corticosteroids are followed by short acting

corticosteroids or prostaglandins 7-12 d later, most cows will calve

2-3 d after the second injection. The interval is shorter and more

predictable with PGF, however, the incidence of calf mortality is

still high.

- Using a combination of corticosteroid plus prostaglandin does not

decrease the percent of retained fetal membranes. However, there are

fewer induction failures, but there is no real advantage.

Problems of pregnancy

Dropsy conditions include hydrallantois and hydramnios.

- Hydroallantois, or hydrops of the allantois, is due to a

defective placenta (the chorio-allantois).

- The fetus is normal.

- The

condition is characterized by a rapid accumulation of watery,

clear fluid, usually in the last trimester.

- The cow is rounded in

the caudal view, and you normally can't palpate the fetus or

placentomes.

- Usually the condition results in a sick cow with

anorexia, decreased rumen motility, dehydration and weakness.

- The

cow may be down.

- The placenta is thick.

- If the cow survives,

postpartum metritis is common.

- The condition usually ends in death

or intervention.

- The prognosis is guarded to poor for life and

fertility.

- Treatment consists of Caesarian section with a slow

drainage of fluid and perioperative support.

- Dexamethasone can be

used if the cow is not down.

- Hydramnios, or hydrops amnios, is due to a defective calf,

usually attributed at least partly to a defect in swallowing.

- The

placenta is normal.

- The condition is characterized by a gradual

accumulation of thick, viscid fluid during the last half of

gestation.

- The cow has a pear shaped caudal view.

- Usually you can

palpate the fetus and placentomes.

- The cow is clinically

otherwise unaffected.

- The pregnancy usually goes to term, and

frequently a small, deformed fetus is delivered.

- Postpartum metritis

is uncommon.

- The prognosis is good for life and fertility.

- No

treatment is required.

- The cow may be allowed to go to term or

induced to calve.

Uterine torsion

- Uterine torsion usually occurs near term and is usually found at

parturition because of the subsequent dystocia.

- The attachments of

uterus and manner in which cows rise are assumed to play a role in

the development of this condition.

- Diagnosis can be made by a number

of ways.

- By manual vaginal exam, the vaginal wall can be felt to be

twisted or spiraled. This can be visualized with the aid of a

speculum.

- By rectal exam, the broad ligaments can be felt to be

crossed and the uterus twisted. The vulva can often be seen to have

a slight twist of the dorsal portion.

- It is important to determine

the direction of the torsion during the examination.

- When correcting

a dystocia, if the calf is found upside down (dorso-pubic), consider

the possibility of a uterine torsion.

- Before and during correction,

insure that things are going in the proper direction.

- If the cervix

is open, a detorsion rod may be used.

- Alternatively, the torsion may

be corrected manually by rocking the fetus until enough momentum is

achieved to flip the uterus.

- If the cervix is closed other methods

must be employed such as the "Plank in flank" method or

surgical (C-section) correction.

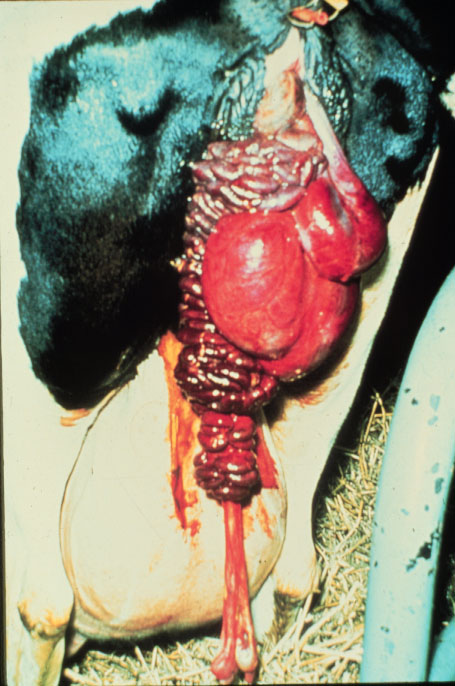

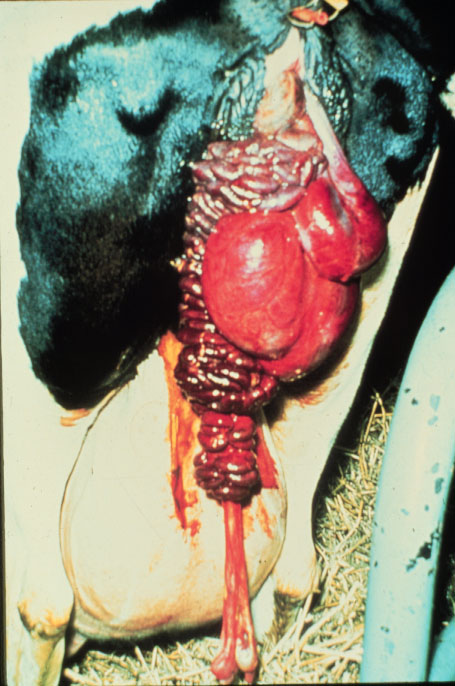

Uterine Prolapse

- Lay terms for this condition include "cast her wethers"

and "lost her calf bed". This is a true emergency.

This is an acute condition that is often associated with

hypocalcemia and may also follow use of great force in fetal

extraction. It is not hereditary.

- Diagnosis is fairly obvious, caruncles can be observed on the

uterus which is prolapsed through the vulva. The prolapse can

involve other organs such as the bladder or intestines. In some

cases, the uterine artery may rupture with fatal consequences.

- The prognosis is relatively good if the uterus does not suffer too

much trauma and is replaced properly. The chance of recurrence not

great. If properly corrected, there are no serious long term

effects, although there may be a slight increase in days open during

that lactation.

- Correction is accomplished by first cleaning

the uterus to remove dirt and accumulated debris.

- Proper restraint

is essential.

- Epidural anesthesia is helpful to prevent straining.

-

To aid in replacing the uterus, tip the pelvis cranially by placing

the cow in a "frog leg" position and elevate the uterus

(either by elevating the hind quarters of the cow or having

assistants hold the uterus up).

- It may help to empty the bladder if

it is trapped.

- Generally the placenta is removed only if loose.

- More

trauma is caused to the endometrium by manually removing the

placenta than by leaving some attached to the uterus.

- Sugar or other

such substances are sometimes used in an attempt to reduce the edema

in the uterus and shrink it down. However, the effect is not

remarkable.

- Oxytetracycline powder or other broad spectrum

antibiotics are sprinkled on the uterus before replacement or placed

in the uterus after replacement.

- Complete replacement is

essential to prevent continued straining and reoccurrence.

- Some

recommend suturing the vulva after replacement with heavy suture

material in something like a large horizontal pattern. Although this

is often done, it is considered a placebo procedure if the uterus

has been properly replaced.

- Oxytocin should be given after

replacement. If given before replacement, the uterus will contract

down and make the job more difficult.

- It is important to treat milk

fever first before replacement because that is a more life

threatening condition.

- Hysterectomy is considered a salvage

procedure.

Vaginal prolapse

- This is often a chronic condition and is hereditary.

- There is a

breed predisposition with Hereford, Santa Gertrudis being

predisposed.

- Vaginal prolapses often recur. For this reason, it is

recommended to cull cattle with a vaginal prolapse.

- They usually

occur prepartum, in late gestation, when the cow is under the

influence of rising estrogen and experiencing relaxation of the

tissues.

- They may occur postpartum or may be associated with

follicular cysts.

- Upon presentation, the vagina, with or without the

cervix, is seen protruding from the vulva.

- The tissue is often dry

and necrotic.

- Tenesmus is common.

- When considering the prognosis,

although rarely life threatening, consider the chance of recurrence

and inheritance and recommend culling.

- These are much easier to

replace but harder to maintain in the correct position.

- Correction is aided and tenesmus reduced with an epidural.

- The

tissue is cleaned,, lubricated and replaced.

- After replacing the

prolapse, the cow may be maintained so that her hind quarters are

elevated (dairy cow)

- These need to be sutured to help reduce the

risk of reoccurrence.

- There are numerous methods of fixation.

- Probably one of the most effective is the Bühner stitch.

- This

requires a Bühner needle and Bühner tape. If other material

such as umbilical tape is used, results are unsatisfactory.

Umbilical tape, for example, will break and also wicks bacteria.

- The Bühner stitch must be removed prior to parturition.

- Minchev's

technique is useful prepartum, especially in cattle that cannot be

watched closely because they are able to calve with the Minchev

buttons in place.

- Tissue trauma, swelling and inflammation may be a

problem.

- Other techniques commonly used include:

- The

"boot-lace", where eyelets are made from hog rings or

sutures. This can be removed temporarily and replaced by lay help,

for example in prepartum cases.

- Modified Caslick's are also used occasionally with varying degrees of

success.

- Pessaries are also used occasionally with varying degrees of

success.

- Trusses, etc. are also used occasionally with varying degrees of

success.

Fetal mummification

- This occurs in cases of fetal death without involution of the

corpus luteum and fetal expulsion, followed by autolytic changes,

absorption of the fetal fluids and involution of the placenta.

- In

cows the maternal caruncle involutes and hemorrhage occurs between

the placenta and the endometrium, leaving a reddish-brown, gummy

mass that imparts a reddish brown color to the mummified fetus.

- The

etiology is varied and ranges from infectious causes such as BVD,

leptospirosis, etc. to non-infectious causes such as genetic,

compressed umbilical cord, etc.

- Diagnosis is based on the presence of a CL, the lack of fremitus

in the uterine artery and lack of fetal fluid in the uterus. The

fetus feels dry and mummy-like on palpation. Oftentimes the head,

ribs, etc. can be felt.

- Prognosis is good if the fetus is removed. After the fetus

is removed, conception usually occurs 1-3 mo. later.

- Treatment is accomplished by administering PGF2a (with or without

estrogen) to lyse the CL. Steroids are ineffective with dead fetus

and non-functioning placenta. After treatment, check the vagina

because sometimes the mummy may be lodged in the vagina when

expelled.

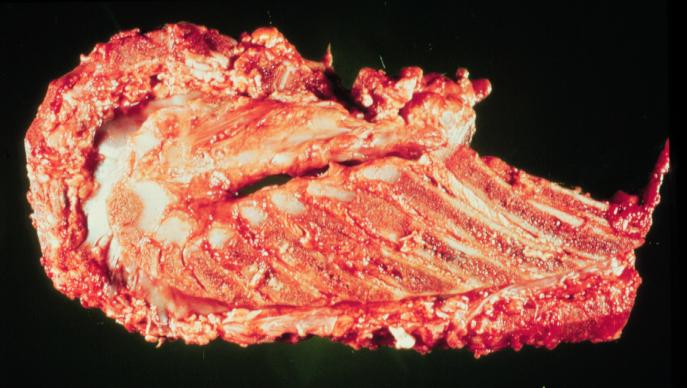

Fetal Maceration

- Fetal maceration results from death of the fetus followed by

dilation of the cervix and incomplete abortion or dystocia, usually

during the last half of gestation. This condition can be due to a

variety of miscellaneous organisms.

Diagnosis

- On palpation per rectum, the uterine wall is thick, little or no

fluid is present in the uterus and you may be able to palpate fetal

bones and pus, or bones crepitating against each other in the

uterus.

Prognosis

- The prognosis is poor for cows with this condition. This is not a

"retained CL" problem so lysis of the Cl is not helpful.

Endometrial damage is present even if all fetal parts are removed.

Treatment

- Treatment is very difficult. The cervix cannot usually be dilated

sufficiently to remove all the fetal parts and any remaining fetal

parts act as an IUD. Surgery has been performed in valuable

individuals but is very difficult.

Calving Injuries

- Postpartum hemorrhage: This can be due to a variety of

causes. When observed, the origin of the blood should first be

determined.

- Lacerations or tears are usually due to mishandling

during OB procedures.

- Tears in the uterus are usually located in dorsally, near

the cervix. They can be diagnosed by palpation or visually.

-

(Sideline: Schistosomus reflexus should be included in the

differential diagnosis when viscera are observed protruding from the

vulva or palpable during an obstetrical procedure.

- This is a

congenital defect where the spine is bent back on itself in a

hairpin turn and the ventral body wall is not closed.

- This defect is

incompatible with life although the calf may be alive at the time of

attempted delivery.

- Delivery requires a fetotomy or cesarian

section.)

- The prognosis in the case of lacerations of the reproductive

tract varies with the location and

extent of the tear.

- Peritonitis is a possible sequela.

- Small tears

may heal without treatment.

- Larger ones should be sutured, either

via laparotomy (difficult) or by intentionally prolapsing the

uterus. This can reportedly be achieved by administering 10 cc

epinephrine i.v., but is not effective after oxytocin

administration.

- Cervical tears can result in profuse bleeding. Not as

critical to future fertility as in the mare but may reduce fertility

depending on the extent. No real treatment, rather try to prevent.

- Vaginal tears are not uncommon. They may go unnoticed

unless they result in hemorrhage.

- There are large arteries at the

1:00-2:00 and 10:00-11:00 positions.

- Otherwise, a vaginal tear may

be noticed because of masses of fat protruding from the vulva after

calving or during a vaginal exam.

- During the postpartum period they

may be suspected during a rectal exam when hard masses are palpated

in the vaginal area.

- Again, the prognosis varies, depending on the

location and extent.

- If significant hemorrhage is occurring, place a

pair of hemostats on the artery for 24 h.

- Attempting to suture the

artery is difficult.

- After 24 h, the hemostats may be removed and

the hemorrhage will have stopped.

- Vulvar or perineal lacerations can be sutured immediately

if seen at parturition, otherwise wait until all the swelling,

inflammation, etc. is gone.

- A laceration in the vaginal or vestibular areas may sometimes

become an abcess. They should be allowed to heal. Many times no

treatment is needed, especially if the dam is not systemically ill.

Caution should be exercised to not transport infective material into

uterus during anytreatments. (For example - a cow is found to have a

foul smelling vaginal discharge but the uterus is normal on rectal

palpation. A vaginal exam should be performed because if the source

is a vaginal tear or abcess, treating the uterus would drag the

infective material into the uterus.)

- Caruncles, if torn during obstetrical procedures can be the

cause of observed hemorrhage. Usually no treatment is needed.

- The umbilical cord will result in bleeding after it ruptures. This

is normal but if significant hemmorhage is observed, you should

verify that the ruptured cord is the source and there are no tears.

|

Bovine

Index

Bovine

Index