Bovine

Postpartum

Problems

335-348 335-348

Postparturient paralysis

- Postpartum paralysis occurs due to trauma and

associated inflammation to the obturator and peroneal nerves.

- Damage

to the obturator nerve causes the cow to be unable to rise and she

will be laying spraddle-legged.

- Damage to the peroneal nerve causes

knuckling.

- The prognosis for these conditions is fair to guarded and

depends greatly on the quality and intensity of treatment.

- Treatment

consists of nursing care and is aimed at preventing the "crush

syndrome" where nerve damage results from the weight of the cow

in prolonged recumbency. Hobbling helps cows with injury to the

obturator nerve to get around.

The postpartum period

- Immediate postpartum care (in chronological

order) consists of:

- 1)calf - check respiration, clean nostrils, rub

skin;

- 2) cow - check for presence of another fetus and damage to the

birth canal;

- 3) calf - disinfect the umbilical cord;

- 4) cow - give

oxytocin, check udder;

- 5) calf - feed colostrum (2 L) within 6

hours,

- check for birth defects.

- The postpartum period spans the time from

parturition to complete involution of the uterus. It can be divided

into 3 periods.

- The puerperal period is the period from parturition

until the pituitary is responsive to GnRH (usually 7-14 days

postpartum).

- The intermediate period begins with the increasing

sensitivity of the pituitary to GnRH and lasts until the first

ovulation (14-20 d pp).

- The post-ovulatory period is the time from

the first ovulation until involution is complete.

Normal involution

- For the first few days after parturition, it is

impossible to palpate the entire uterus, but you can feel a thick

uterine wall and longitudinal ruggae. A thin walled, flaccid, smooth

uterus is abnormal.

- By approximately 2 weeks postpartum you should

be able to palpate the entire uterus. A discharge (called "lochia")

is normal during this time. It should be odorless, thick, reddish

(tomato soup), and may have white flecks. The caruncles will slough

around 7 days postpartum. The fluid should be gone by 18 days and

the uterus normal size by 5 weeks. Epithelization of the caruncular

sites is complete by 40-50 days.

Abnormal

postpartum period

- One of the main causes of abnormal involution

is an unsuitable calving environment.

- The ideal environment is a

sunny, grassy well drained pasture.

- When cows are calved repeatedly

in a confined area, "Seeding" of the area with pathogens

may occur, thereby increasing the incidence of postpartum metritis.

- Inappropriate obstetrical practices, abortion diseases and retained

placenta may also contribute to the problem.

- An abnormal postpartum

uterine involution is often associated with other primary problems,

e.g. LDA, ketosis, mastitis.

- Dairy cattle tend to have a higher

incidence of postpartum problems than do beef cows.

- Many problems

can be prevent by hygiene.

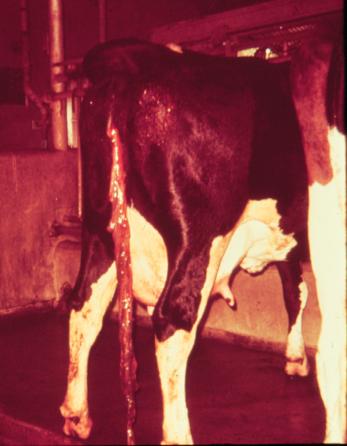

Puerperal metritis

- This condition occurs within the few days just

after calving.

- Clostridia

is often involved but other pathogens such as coliforms, etc. may be

involved as well.

-

Puerperal metritis is associated with uterine

atony or inertia, with or without retained fetal membranes.

-

Cows

will be systemically ill.

-

They will exhibit depression, anorexia, GI

atony, agalactia, will be febrile, and may have peritonitis.

-

The

uterine discharge will be fetid, foul-smelling, watery, and

reddish-black.

-

The uterus will be thin walled and atonic.

-

This

disease can be life threatening.

-

Treatment should include both

systemic plus

intrauterine antibiotics.

-

Systemically, penicillin is a good choice,

while tetracycline is best intrauterine.

-

The uterus will be friable

so care must be taken with intrauterine treatments.

-

Uterine lavage,

consisting of draining off the fluid and flush the uterus

atraumatically, helps to reduce the amount of debris and bacteria

within the uterus.

-

Uterine ecbolics, such as oxytocin or ergonovine

maleate may help to stimulate uterine contractions and prevent

buildup of more fluid.

Postpartum metritis

- The key differentiating feature between common

postpartum metritis and puerperal metritis is that cows with common

postpartum metritis are not clinically ill.

- In most cases, the

following bacteria which have a somewhat synergistic relationship

are found in the uterus.

- Fusobacterium

necrophorum

produces a leucotoxin,

- Bacteroides

melaninogenicus

and fragillus

produce and release a substance which prevents phagocytosis.

- Actinomyces

pyogenes

produces a growth factor for Fusobacterium.

-

Other bacteria can cause a postpartum metritis but rarely persistin

the uterus, cause permanent damage or infertility.

- Incidental

bacteria are usually gone from the uterus by 3 weeks.

- A.

pyogenes

causes extensive damage if present for greater than1 week. After

clearing the uterus of A.

pyogenes

it takes at least 1 mo. to resolve the damage and restore fertility.

- The problem of delayed involution or metritis

is usually detected on rectal palpation.

- Often no systemic signs are

seen.

- A purulent discharge may be observed.

- Upon vaginal speculum

exam a discharge from the cervix, along with inflammation of the

cervix and vaginal wil lbe seen.

- In a California study they concluded

that a speculum exam was better than palpation for the diagnosis of

metritis.

Treatment

- Treatment will vary depending on the particular

situation (cow, client, etc.).

- One alternative is to do nothing,

just monitor the cow and intervene only if she shows systemic signs

or the condition persists at the end of the Voluntary Waiting

Period.

- Cows seem to do as well with non-intervention as with

aggressive treatment and the problem of withholding milk because of

residues is avoided.

- Another treatment alternative which does not

involve dumping milk is ProstaglandinF2alpha.

- Studies have shown that treatment with Prostaglandin gave equal or

greater fertility than that obtained after intrauterine therapy,

regardless of the drug used IU.

- In addition to causing luteolysis,

Prostaglandin may stimulate myometrial contractions, may stimulate

phagocytosis by uterine leucocytes and decreases progesterone

inhibition of uterine defense mechanisms.

- Other hormones which have been used include:

- Estrogens, are sometimes used because they

stimulate uterine defense mechanisms, however there is concern that

they also open the utero-tubal junction.

- Long acting forms (such as ECP) may result in

salpingitis, myometrial infection, and subsequent decrease in

fertility. It has been reported that 5 mg estradiol benzoate given

after 5 d postpartum increases uterine phagocytosis without

undesirable side effects.

- The potential benefits of GnRH are related to

the involution of the uterus and the level of management. Use of

GnRH during the postpartum period may result in an increase in

pyometras.

- Intrauterine antibiotics:

- Oxytetracycline intrauterine is effective, but

there is some concern that it may decrease uterine defense

mechanisms.

- Although it is slightly compromised by organic debris,

you can achieve MIC in the uterus with intrauterine administration,

but not with systemic administration without nephrotoxicity.

- Not shown to improve

reproductive efficiency

- None aproved

- Other antimicrobials are generally not as

effective as tetracycline.

- The aminoglycosides are not recommended.

They require an aerobic environment, but the uterus is anaerobic.

The presence of organic debris inhibits their efficacy. Importantly,

their use in food animals is prohibited.

- The sulfonamides are

ineffective in the presence of organic debris, of which there is

usually copious amounts.

- Penicillins are usually ineffective by the

intrauterine route because penicillinase producing organisms are

present early on (during the first 3 weeks).

- In the past,

nitrofurantoins (nitrofurazone) has been widely used as an

intrauterine infusion, however it is ineffective in the presence of

organic debris and you cannot achieve the MIC in the uterus.

Moreover, it is labelled as "Not for use in food producing

animals".

- Exenel (ceftiofur) -

- 2.2 mg/kg SID

5days efective

- Approved for metritis

- No withdrawl

- Cure rate for the 1.0 mg ceftiofur

equivalents/lb (2.2 mg/kg) BW dose group was significantly

improved relative to cure rate of the negative control on

day 9.

- Ceftiofur hydrochloride administered

daily for five consecutive days at a dose of 1.0 mg

ceftiofur equivalents/lb (2.2 mg/kg) BW is an effective

treatment for acute post-partum metritis.

Retained Fetal Membranes

- This is usually defined as failure of placenta

to be released by 12 hours postpartum, although some use 24 hours as

the cutoff.

- The incidence generally ranges from 5-10% in dairy

cattle to 1% in beef. In cases of induced parturition the

incidence increases to 30-100%.

- The detrimental effects come about

primarily as a result of the metritis caused by the retained

placenta.

- This is manifested by an increase in the days to first

service (4 days), an increase in days open (19-35 days), and an

increase in services/conception (0.2).

- There are multiple etiologies

which may be involved.

- Basically they relate to a disturbance in the

loosening mechanism in the placentomes or uterine inertia.

-

Separation of placenta requires a series of events beginning with

prepartum maturation of the placenta. During parturition, there is

mechanical detachment of the cotyledon by uterine pressure, followed

by anemia of the fetal villi after fetal expulsion and a reduction

of the size of the caruncles during postpartum uterine contractions.

Myometrial activity decreases by 24 hours after parturition and

almost ceases by 48 h, so if expulsion has not occured by 24 hours,

it is unlikely to occur until progressive liquefaction and expulsion

6-10 days later.

- There are some specific causes of retained

placenta, including premature delivery, infectious diseases,

metabolic/nutritional causes, hormonal causes and uterine inertia.

- Diagnosis is usually obvious. Retained placenta

may cause decreased appetite and decreased milk yield resulting from

acute metritis.

- Treatment decisions, although maybe considered

somewhat controversial, should be based on "do no harm".

-

If left alone, the placenta will usually drop approximately 5 days

postpartum.

- If treated, they often take longer to be released

because of reduced autolysis.

- Conservative treatment consists of

trimming the membranes off at the vulva and monitoring TPR,

appetite, milk production, attitude, etc.

- Antibiotics should be

given if the cow is sick (see puerperal metritis).

- Oxytocin is often

recommended, especially in the first 24 hours, although it may be

beneficial for 4-7 days. It has been shown to increase phagocytosis

by uterine neutrophils for up to 8 days but has not been shown to

hasten release of a retained placenta.

- Manual removal is not

advised.

-

Manual removal is associated with decreased fertility.

-

Numerous studies have looked at manual removal vs. other treatments

or no treatment at all and in every case manual removal had a

negative effect on future reproductive parameters.

-

The use of

chemotherapeutic agents may actually prolong the condition by

interfering with uterine defense mechanisms or inhibiting the lysis

of villi.

-

Antibiotics, hormones, including estrogens (see above),

prostaglandins and oxytocin have all been used in various dosages

and treatment schedules all without significant effect on releasing

retained placentas.

-

Basically, if the cow isn't sick, leave her

alone, if she is clinically ill, treat the illness.

- Prevention is recommended.

- Try to have dietary

calcium <100 g/d for the last few wks of the dry period.

- Vitamin

E at a level of 0.74 g/d per os during dry period

- Se at 0.1

mg/kg i.m., 21 days prepartum will lower the incidence of retained

placentas.

- A good review of this subject is: Paisley

LG, Mickelson WD, Anderson PB; Mechanisms and Therapy for Retained

Fetal Membranes and Uterine Infections in Cows: A Review.

Theriogenology 25 (March 1986):353-381

Pyometra

-

Accumulation of pus in the uterus

-

Retained CL

-

Anestrus is the primary clinical sign. There is no

vaginal discharge

-

Etiology

-

Postpartum - fluid or infection in the uterus when

ovulation and CL forms.

- Early ovulation or delayed fluid clearance

may increase the problems

- Postcoital - almost pathognomonic for

Trichomoniasis

-

Diagnosis

-

Rectal palpation

-

Fluid filled uterus, fluid flows from horn to horn

-

CL present

-

Absence of positive signs of pregnancy (diff dx)

-

Vaginal exam (cervix usually closed)

-

No systemic signs

-

Treatment

-

Estogens 50-65% effective

-

PGF2a 85-90% effective - increase efficacy if treat 2

days in a row

-

Intrauterine infusions

|

Bovine

Index

Bovine

Index Bovine

Index

Bovine

Index