|

Equine

Pregnancy

103-153,

157-165, 177-178 103-153,

157-165, 177-178

Physiology of

Pregnancy

The Early

Embryo

-

At about 24 hours post

ovulation the embyro is at 2 cell stage

-

4-5 days - morula

-

5-6 days blastocyst

-

5-6 days enters uterus

and zona shed

-

Capsule forms at

blastocyst stage

-

Migration to day 16. The

embryo migrates in the uterus for approximately 16 days to release a

'signal' that pregnancy is established. Fixation

of the embryo (gestational sac) occurs at about 16 days post ovulation.

Endometrial cups

-

At

about 36-38 days, fetal tissue along the chorionic girdle begin to invade

the endometrium and form the endometrial cups.

-

Endometrial

cups secrete eCG ...Equine Chorionic Gonadotrophin (formerly PMSG...Pregnant

Mare Serum Gonadotrophin). This acts to

luteinize the normal follicular waves that are occurring and results in

formation of the secondary corpora lutea.

-

The

cups remain, even if the pregnancy is

lost, and are then sloughed at the

normal time (120 days).

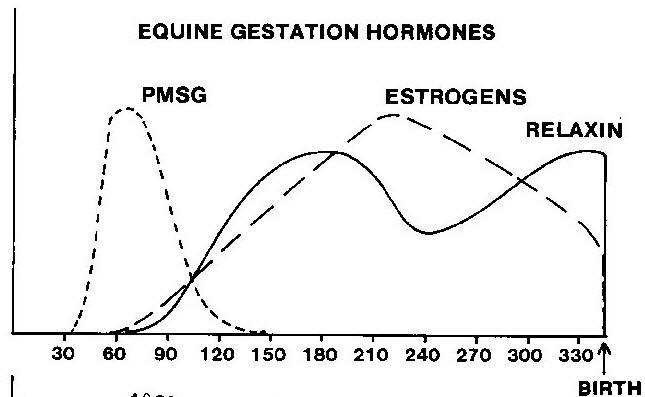

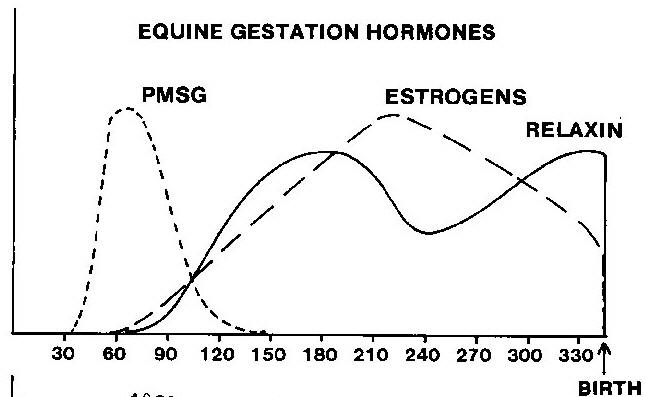

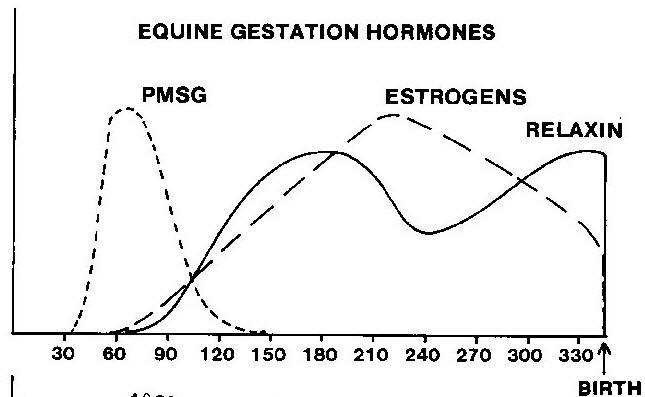

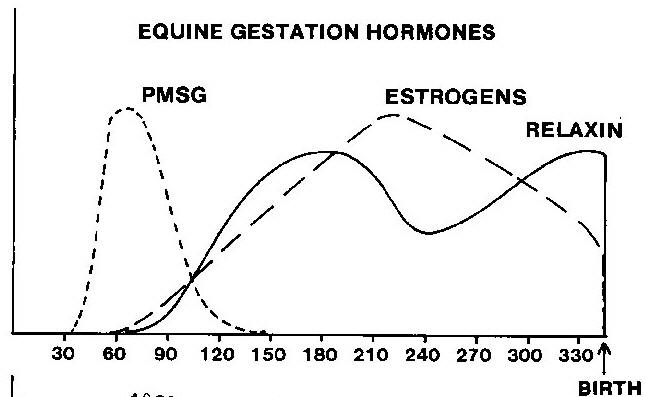

Equine chorionic gonadotropin (eCG): (formerly

pregnant mare serum gonadotropin or PMSG)

-

Produced by the endometrial cups beginning around d

37-42, peaking around d 60-80, after which the endometrial cups start to

decline, disappearing around d 120-150.

-

The function of the endometrial

cups and eCG are unclear.

-

Some hypothesize an immunologic role in helping to

maintain pregnancy.

-

Causes luteinization of follicular waves to create

secondary CLs.

-

Although eCG has an FSH-like action in many other

species, it has LH-like activity in mares.

Secondary CLs

- The

secondary CLs result in progesterone rise about day 60-120. The

endometrial cups regress (they are sloughed from the uterus by an

immunologic response).

- Secondary vs. accessory CLs (ovulatory

or anovulatory)

Progesterone/Progestagens:

-

Progesterone initially rises, followed by a slight decrease then rises to a peak at d 80, then gradually declining to 1-2 ng/ml during mid-late

gestation (d 150).

-

The second rise is associated with the formation of

accessory and secondary CL.

-

The 5 alpha pregnanes rise from mid

gestation to term.

- Produced from maternal cholesterol

-

The fetoplacental unit produces sufficient

progestagens so that ovariectomy can be performed after 120-150 d.

- Late gestation progestagen rises (last month of

pregnancy)

- From fetal adrenal production of 5

alpha reduced pregnanes (adrenals do not have 17 alpha

hydroxylase)

Estrogens

- Mare

ovarian estrogens begin to rise at day 38-40.

- From gonadotrophic stimulation of luteal

tissue

- Late in

gestation maternal estrogen production rises.

- At

day 70-80 a second rise of estrogens from the fetal-placental unit occurs.

-

Placental aromatization of the common C-19 precursors

-

dehydroandrosterone (DHA) and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)

-

Secreted by fetal gonads.

Placenta

- The

placenta takes over progestagen (not progesterone) production until

foaling. Therefore, a mare does not need her ovaries after about 120

days of gestation.

- The mare has diffuse type of microcotyledonary

placenta

- Complete placental formation is done at 150

days.

|

Equine Placentation adopted

from Ginther |

|

Day 9-10

Inner cell mass (brown)

Yolk sac starting |

|

Day 14

Still mobile

Mesoderm will be blood vessels and connective tissue.

|

|

Day 16

Folds start to form over embryonic disc to form amnion. |

|

Day 48-19

Amnion has formed.

Note the two and three layered areas.

|

|

Day 21

Allantois is emerging. |

|

Day 25

Allantois has moved over embyro.

Heart beat present.

Note red developing chorionic girdle. |

|

Day 30

Note red chorionic girdle which will form the endometrial cups. |

|

Day 40

Embryo moved to opposite pole.

Yolk sac replaced by allantois. |

|

Day 80

The yolk sac is only a remnant.

Conceptus fills both horns. |

Pregnancy

Diagnosis

- Certain characteristics

of pregnancy in the mare aid in diagnosis.

- Progesterone causes increased

tone of the uterus and cervix.

- Estrogen from the conceptus, in

conjunction with the progesterone results in exaggerated tone.

- The

vesicle is spherical and distinct, and can be palpated from 18 d (+)

through 60-70 d, and seen with ultrasound beginning at 10 or 12 d

(depending on the machine).

-

Other significant characteristics of equine pregnancy

include the presence of chorionic girdle cells from the fetal

trophoblast which invade the endometrium. The ovaries are active during

pregnancy, with large follicles palpable especially around 18-23 d and

36-45 d.

Hormones

Estrogens

Click on the BET labs icon to see their web page and find out what

hormones they run.

External signs of pregnancy

- Although

abdominal enlargement is characteristic of pregnancy, it is unreliable

as a diagnostic sign.

- Ballotment or observed movements of the fetus can

often be seen late in gestation.

- Mammary changes are quite variable.

-

Pelvic changes (relaxation of the pelvic ligaments) occur late in

gestation but are often difficult to detect.

-

Cessation of estrus

behavior is variable and unreliable.

- Some mares will continue to show

estrus even when pregnant.

Methods of

diagnosisPalpation

per rectum

- Cervical changes from 16 or 17

d to term are elongation, firmness and tubularity. The uterus also has

increased tone.

- The chorionic vesicle is distinct and spherical

and approximate sizes are:

- 28 d (4 wks)

Key lime (pullet egg)

- 35 d (5 wks) lemon

-

42 d (6 wks) orange

- 49 d (7

wks) grapefruit

- 56 d (8 wks) cantaloupe

-

By 90 d it is hard to delineate the cranial margin of

uterus.

- Fetal Ballotment per rectum becomes

consistent after 150d.

- Aging fetus by size, as

in the cow, is imprecise.

- Differentials which

may confuse the examiner include the bladder and enlargement in the non

pregnant tract at the base of the uterine horn.

Ultrasound

- The

time of earliest diagnosis depends on the MHZ of the probe.

- Gestational

age can be estimated from the size of the vesicle.

- There is a plateau in

the growth curve between d 17-24 during which the size does not increase

much.

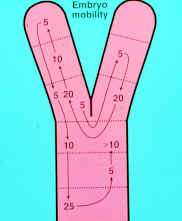

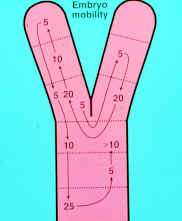

- Movement of the

vesicle is characteristic of early pregnancy, covering the entire uterus

and moving surprisingly rapidly.

- Movement ceases around d 16-17 when

"fixation" occurs.

Movement of the equine embryo.

-

The fetal heartbeat can be observed around d 23-24.

- The vesicle

undergoes a series of changes, having a very characteristic appearance

at various stages with which the examiner should be familiar.

- The

vesicle usually becomes fixed in a location at the base of a uterine

horn.

- Although initially spherical, the shape becomes more triangular

around d 18 and the embryo becomes visible around d 20-21, usually in a

ventral location.

- Changes in the shape of the vesicle and the

characteristic location of the embryo are related to the developing

trophoblast.

- At d 21, the embryo is at the bottom of vesicle and the

entire hypoechoic structure is the yolk sac.

- Soon thereafter the

developing allantoic membrane can be seen.

- By d 30 the embryo is found

in the middle of the vesicle suspended by the developing allantoic

membrane, with the allantoic sac beneath and the yolk sac above.

- By d 36

the embryo is near the top of the vesicle and the yolk sac is all but

gone.

- By d 40 the embryo is back in the middle of the vesicle, suspended

by the umbilicus.

-

Vesicles that are smaller than

normal size for their age are associated with increased rates of

embryonic loss.

-

One of the critical reasons for a thorough early

pregnancy exam is to detect twins, which will be discussed in more

detail later.

Fetal sexing

-

Fetal sexing is becoming more and more in demand.

-

Numerous reasons exist

for owners desiring knowledge of the sex of the fetus, such as

appraisals, insurance coverage, payment of stud fees, sales

consignments, mating lists, sale or purchase, etc.

-

The veterinarian

performing fetal sexing should be aware of the liability implications

involved.

-

Gender determination is based on the location of the genital

tubercle.

-

The genital tubercle is the precursor of the penis in the male

or the clitoris in the female.

-

The tubercle migrates toward the

umbilicus in the male and toward the anus in the female.

-

Ideal times for

performing the procedure are from 59 to 68 days or 5 to 6 months.

-

Before

58 days the tubercle is not distinct enough and has not migrated

sufficiently to make a distinction.

-

After 70 days the fetus is hard to

reach until it is approximately 3.5 to 4 months of age.

-

As the fetus

gets larger, a trans-abdominal approach may be preferred.

-

It is important

to mention that accuracy is based on certainty and that the veterinarian

should keep their own written records. If cattle are available, it is

easier to learn the technique on cattle because the manipulations are

easier and they are more tolerant of prolonged rectal examinations.

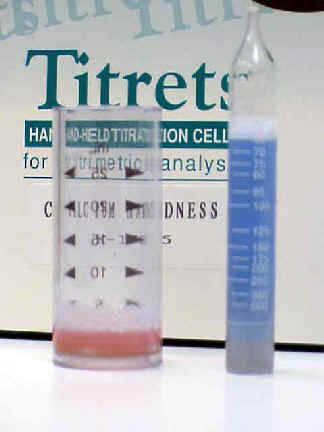

Indirect pregnancy tests

-

The

presence of eCG has been used as a test for pregnancy because it is only

found in pregnant mares.

-

The problem is that it remains elevated after

the cups are formed even if fetal death occurs. In house tests are

available which makes them attractive in some situations (e.g. miniature

horses).

-

For example, with the Synbiotics test, it is reported that 20%

of samples are positive at 30 d, 66% at 38 d, 76% at 40 d, and 92% at 42

d.

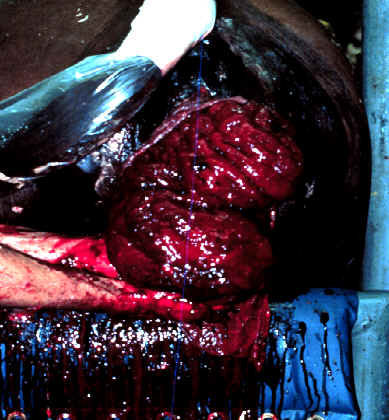

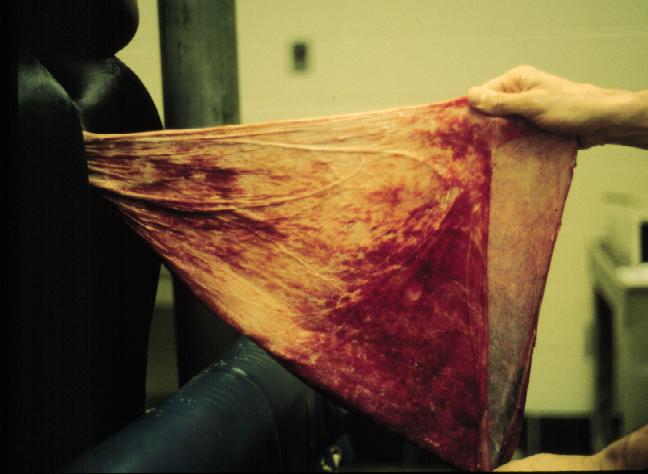

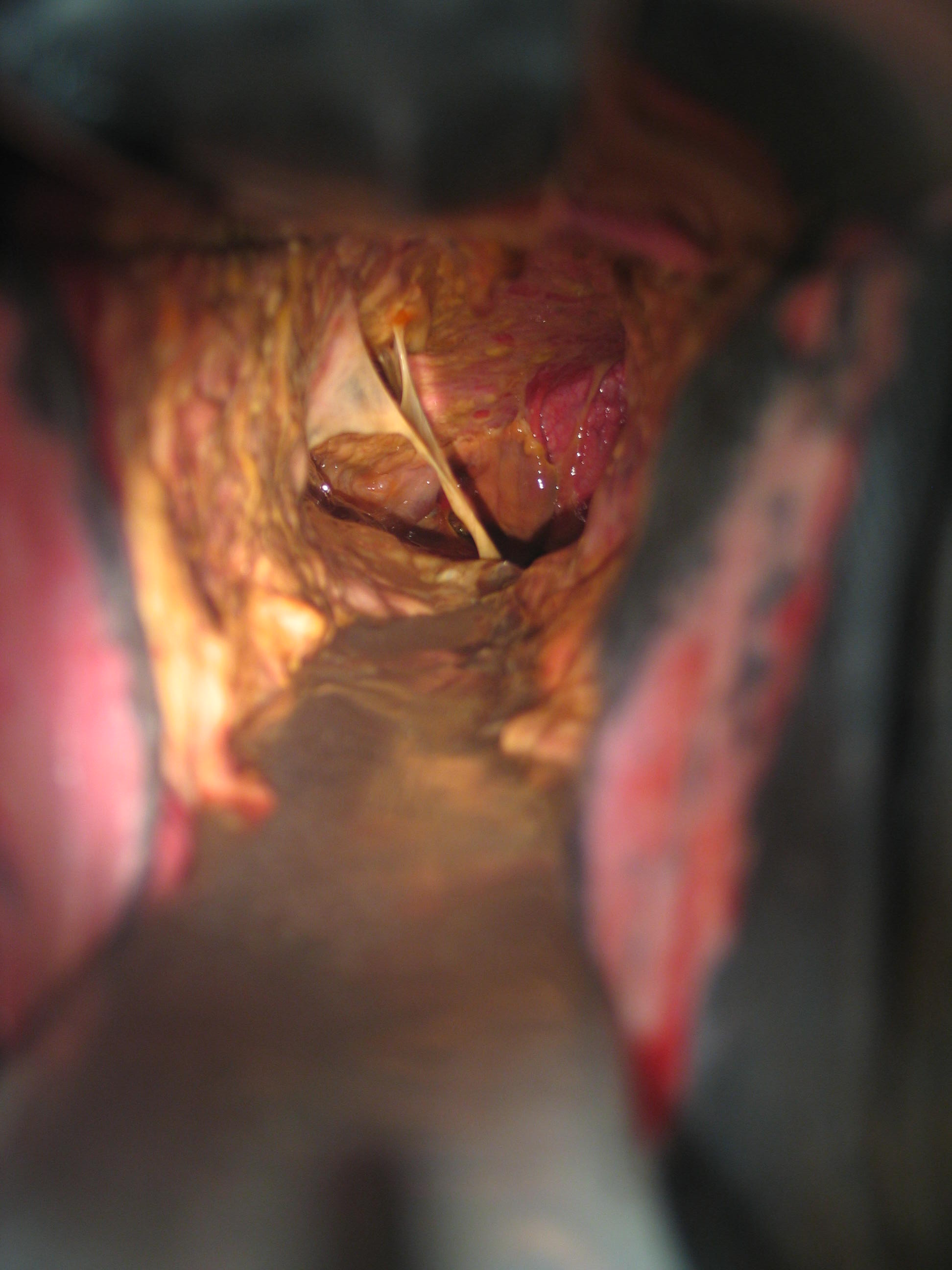

Endometrial cups in a mare.

-

Estrogens are elevated 150 d to term

(due to

production from

fetal gonads).

-

The Cuboni

test, based on fluorescence of urine, is 90% accurate after 100 d,

100% accurate after 150 d.

-

Generally, that late in gestation, other

means of pregnancy diagnosis have already been employed.

Cuboni test.

-

Estrone sulfate can be tested for in almost any

bodily fluid. In serum there is a sharp rise after 60 d, peak levels by 80

d.

-

Before 60 d a false positive can be obtained due to estrus. In milk a

similar pattern is observed, only with lower values.

-

It is

considered

an indicator

of fetal

viability

after 44 d.

In feces, it

can be found

after 4 mos.

And can also

be found in

urine.

Testing is noninvasive and therefore

used in studies of wild equids.

-

Commercial tests available "Equi Test - ES" (www.trideltaltd.com);

"Confirm"

(http://www.icpbio.com/site.aspx/Pages/Products/ConfirmEquine)

-

Early

Pregnancy Factor

Check

this link out to a potentially exciting method to determine

pregnancy.

- EPF - two components

- EPF-A - Uterine tube

- EPF -B - Ovary

- Production requires signal from fertilized ovum (ovum factor)

released under prolactin presence after sperm penetration.

- Appears 4-6 hours

- Disappears with fetal death

- Non-detectable at 20 days in milk and 30 days in serum

- Lateral flow dipstick test

- It does not work in the cow, so I have

doubts in the mare.

- I have seen no refereed papers about its use

in the mare.

Problems of

Pregnancy

Uterine

torsion

- Uterine torsion is an uncommon

problem, found usually late in gestation (7 mo to term) but not usually

at parturition (unlike the cow).

- It is thought that the reduced

incidence in the mare can be attributed at least in part to anatomical

differences from the cow in the attachments of the uterus to the body

wall by the broad ligament and to the method of rising (front end first

as opposed to cow).

- The clinical signs are those of colic.

- Diagnosis is

made by rectal palpation.

- The broad ligaments are crossed, one going

over the uterus, the other below.

- The location of the ovaries is

abnormal as well.

- A vaginal exam is usually not very helpful, as the

vagina and cervix are rarely involved.

- Treatment is generally surgical

via either a standing flank laparotomy or midline laparotomy.

- After

correction, the pregnancy is allowed to continue to term.

- Rolling has

also been reported (JAVMA 193:3, p337).

- In that report, 6 of 7 were

successfully corrected, with 1 uterine rupture (355 d gestation,

previous attempt at correction).

Prepubic tendon rupture

- More

commonly seen in older, heavier (draft) mares, it is not common in

athletic breeds.

-

There is

probably not

really an actual

pre-pubic

tendon. It is

really a tear in

the muscle.

- The first sign is ventral edema.

- This is followed by a

"Dropped" abdomen.

- The mammary secretions may become bloody.

-

Treatment consists of abdominal support and reducing activity.

Parturition or induced or assisted or an elective C-section

has been the

traditional

treatment. A report from U Penn

(JAVMA

232:257-261,

2008) indicates that a

conservative

approach (wait

and let the mare

foal) may result

in better mare

and foal

prognosis.

- The prognosis is poor for survival of

both the dam and the fetus.

Obstetrics

- Normally parturition occurs at night,

and the mare seemingly can delay parturition until the setting suits

her.

- Horses have a very variable gestation length (ave 335, range

305-405).

- It is a very rapid process. Often being completed in less than

20 min.

Signs of impending parturition in the

mare

- Udder development is evident 3 to 6

wks prior to foaling.

- "Waxing" or the presence of a very thick

drop of sticky colostrum at the teat end, can be observed 1-72 h prior

to parturition.

- Some mares may leak colostrum for days, to the extent

that insufficient good quality colostrum is available when the foal is

born.

- There is slight relaxation of the sacrosciatic ligaments but this

is not as evident as in cows, especially in the heavily muscled breeds

like Quarter Horses.

- The vulva becomes edematous and lengthens.

- Most

importantly, there is a change in the electrolytes in the mammary

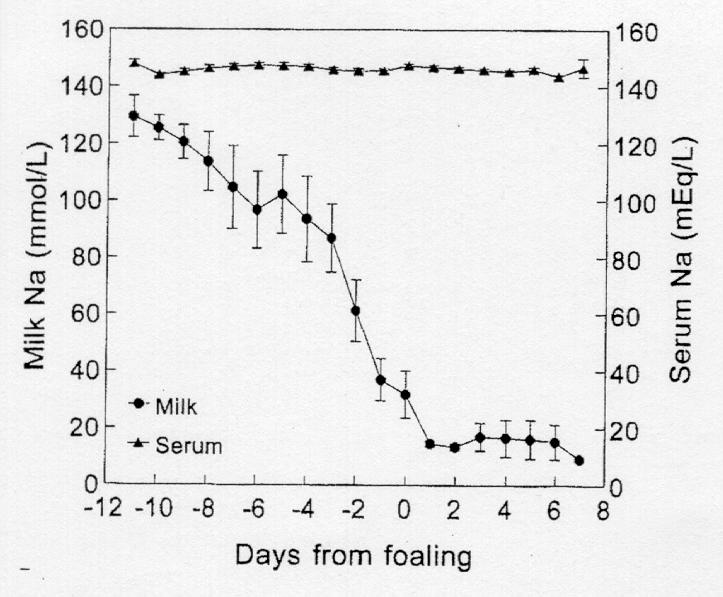

secretions.

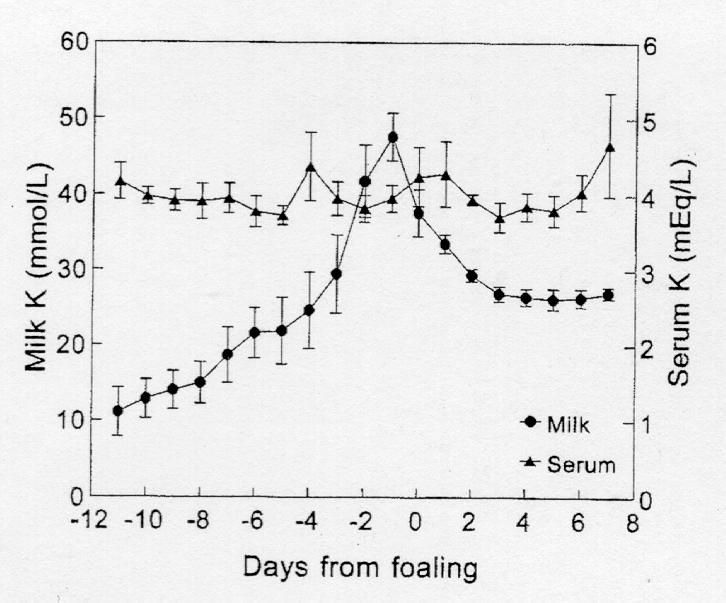

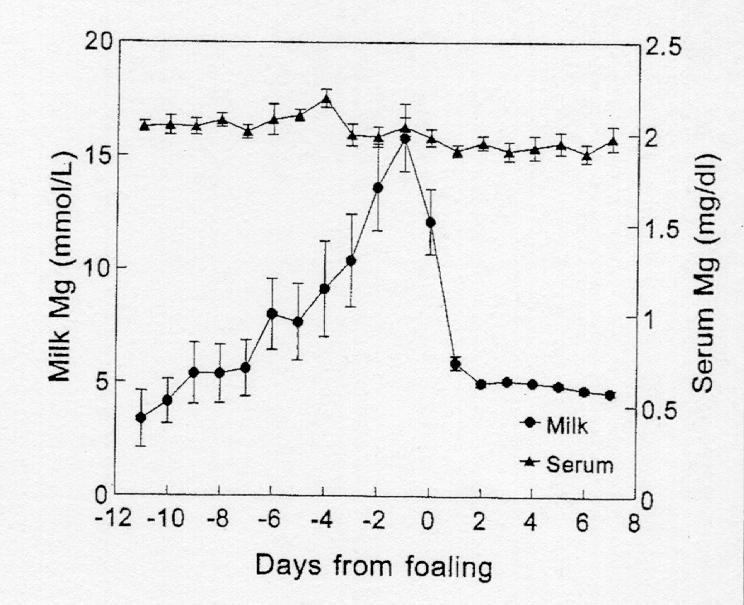

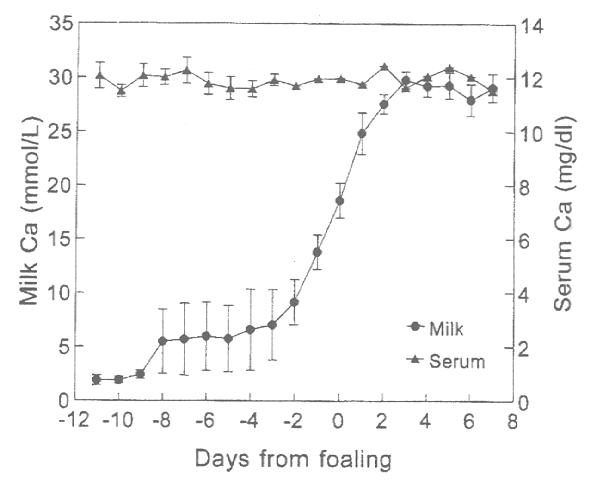

- Potassium and magnesium increase,

- Calcium increases sharply.

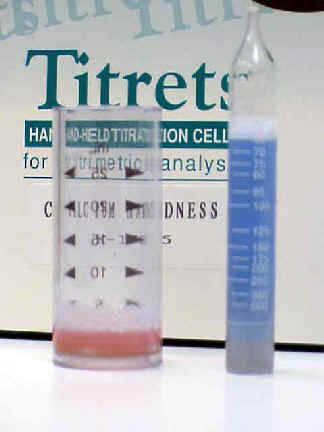

- A point system based on these changes was

developed by Ousey et al. to aid in predicting foaling. Others watch for

the crossing of the sodium and potassium curves in addition to elevated

calcium.

|

Calcium

mmol/L

|

Sodium

mmol/L

|

Potassium

mmol/L

|

Points |

|

> 10 |

< 30 |

> 35 |

15 |

|

> 7 |

< 50 |

> 30 |

10 |

|

> 5 |

< 80 |

> 20 |

5 |

- The most important

change is an increase in divalent cations (Ca++, Mg++) in milk.

- The

increase in magnesium is more gradual and occurs earlier pre-partum

than Ca++. It is the increase in Ca++

that is most useful.

- When calcium rises >10 mmol or 400 ppm,

parturition is imminent.

Characteristics of parturition in mares

-

Stage 1 is characterized by restlessness, walking,

frequent urination, sweating, the mare is anxious, looking at her

abdomen, getting up and laying down, rolling.

-

Most mares will rise at

least once after going down, but repeatedly getting up and down may

signal a problem.

-

The foal has an active role in its final positioning,

going from dorso-pubic to dorso-sacral.

-

The duration of Stage 1 is

usually about an hour or a little longer (10 min - 5.5 h).

-

Stage 1 ends

with the rupture of the chorio-allantois at the cervical star.

- Stage

2 consists of 15 to 30 min of very forceful expulsive efforts.

- The foal

is presented in the intact amnion, usually with one forelimb about 6 in.

behind the other.

- The long umbilical cord remains intact until the mare

rises.

- It was once thought that significant blood flow, up to 1 liter,

occurred through the cord after birth and people were cautioned about

breaking the cord too soon.

- However, more recent studies have shown that

there is no significant blood flow in the cord after birth and there is

no difference in the PCV between foals in which the cord is broken soon

after birth and those in which the cord is left intact.

- Stage

3 typically appears as a tranquilizing effect post-delivery.

- The

placenta is usually passed in less than 3 h after parturition.

- After

delivery, the navel should be disinfected with 2% chlorhexidine.

-

Non-tamed iodine is associated with an increased incidence of patent

urachus, and other problems because it is too harsh.

- Povidone iodine

does not disinfect adequately.

- Good colostrum

has a specific gravity >1.06 and adequate intake should be observed.

Inspection of the placenta should be routine.

-

Make

sure that all the placenta has been passed.

-

Check for signs of

placentitis. Any abnormal areas may indicate septicemia of the foal.

-

Treatment should begin immediately, before clinical signs appear in the

foal. Also check for other abnormalities in the placenta. Areas of

aplastic or hypoplastic villi are an indication of uterine pathology.

Dystocia

- Considerations

to keep in mind in the management of dystocia are that the process of

parturition is very rapid and very forceful.

- The reproductive tract of

the mare is easily traumatized. Mares can be unpredictable during

dystocia and it is advisable to use caution.

Guidelines on when to intervene:

-

After 10 min of strenuous labor and no sign of the

fetus perform an examination.

-

If the forefeet and muzzle are in the

canal, allow the mare to continue.

-

After strenuous contractions for

another 10 min, assist delivery.

-

The amnion, which is a white membrane,

should protrude from the vulva within 5 min of rupture of the

chorio-allantois.

-

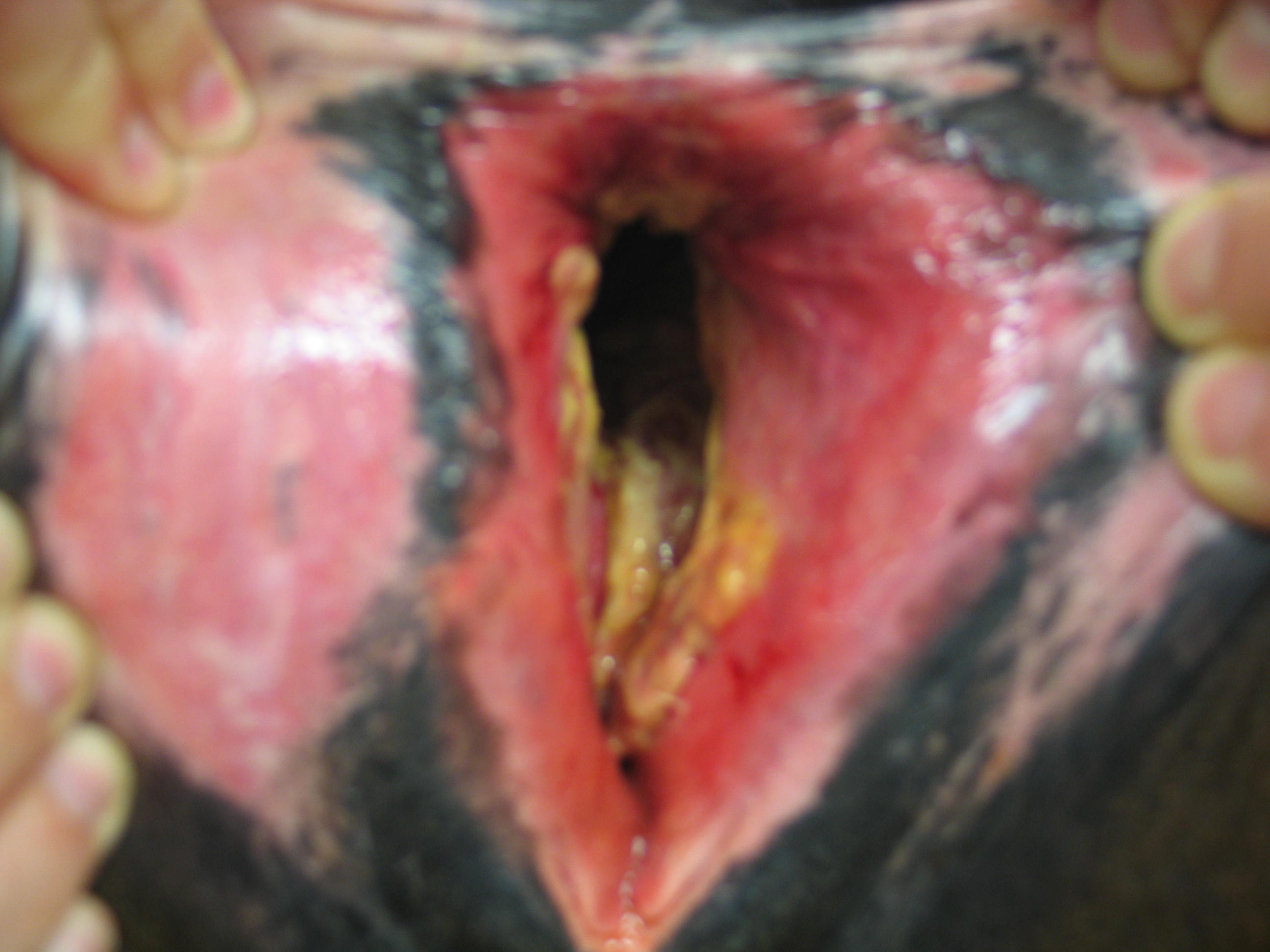

If a red velvety membrane (the chorio-allantois) is

seen at the vulva, a true emergency exists. This is termed 'red

bag'.

-

Unfortunately, if

intervention is needed, oftentimes the foal will be dead.

-

Assistance

must be given rapidly if the foal is to be saved.

-

A weak or dead foal

cannot assist in the process of parturition.

Proper restraint, both physical and chemical are

important.

- Minimize the use of drugs that

will affect the CNS and cause respiratory depression of the foal.

- For

sedation or tranquilization, acepromazine is not recommended if the foal

is alive because of its long clearance time.

- Barbiturates are also not

recommended because of severe fetal depression, even with doses that

don't affect the mare.

- Both xylazine and detomidine can be reversed with

yohimbine (0.05 mg/lb, IV).

- Caution should be exercised if xylazine is

used alone as it will sometimes result in hypersensitivity of the

hindquarters.

- Epidural anesthesia is not recommended because it takes

too long to take effect, doesn't stop the abdominal press and may cause

the mare to be unstable in the hindquarters if she ends up needing to be

shipped somewhere or during recovery if she undergoes general

anesthesia.

- Short term field anesthesia can be

accomplished with xylazine (1 mg/kg IV) or detomidine (10 µg/lb, IV)

followed by ketamine (2 mg/kg IV) after the mare drops her head. Then

administer "triple drip": 5% glycerol guaiacolate (GG)

solution containing 0.5 mg/ml xylazine (or 20 µg/ml detomidine) plus 1

mg/ml ketamine administered at approximately 1.0 ml/lb/hr (if give a

second bag use 0.25 mg/ml of xylazine).

- If the

foal is dead, you can use glycerol guaiacolate and thiobarbiturate.

-

For Caesarian section: give GG (5% Sol.) to effect,

then ketamine (1mg/lb) then intubate (Isoflurane preferred over

Halothane); if pre-medication is desired, 50 mg valium can be given IM,

10 mg butorphanol IV.

- After delivery, give the

foal Dopram (0.2 mg/kg, IV) and yohimbine if needed.

Cleanliness and lubrication are absolutely

essential in the management of equine dystocia.

- Petroleum

jelly is a good choice of lubricant.

- Water soluble lubricants are

acceptable but must be replenished more often.

- Do not use a detergent as

a lubricant because it has a de-fatting action on the tissues.

-

Do

not

use

J-lube,

particularly

if a

C-section

may

be

anticipated.

J-lube

has

been

found

to

be

quite

toxic

if

in

the

peritoneum.

Prompt assessment of the cause of dystocia is

important as is relatively rapid decision making as to the course of

action.

- Abnormal fetal posture is the most

common cause of dystocia because of the long extremities and neck of the

foal.

- Normally, the foal is an active participant in parturition.

- A weak

or dead foal fails to participate in the process.

- Congenital deformities

such as wry neck, contracted tendons or ankylosis result in dystocia.

-

Dog sitting posture, foot-nape presentation (often causing a

recto-vaginal laceration if not corrected) and nape presentation are

fairly common problems.

- Abnormal presentation, e.g. posterior or

ventral-transverse also may be encountered.

- Twins frequently result in

dystocia.

- Maternal causes, such as a tight vaginal-vestibular sphincter,

a small vulva or Caslick's that was not opened may also be involved.

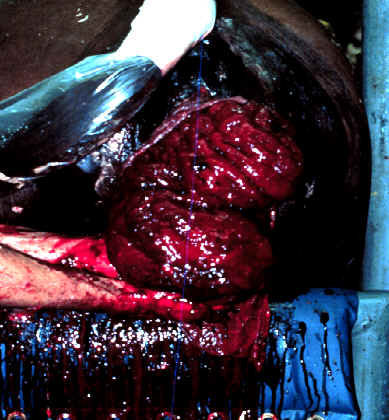

Premature separation of the chorio-allantois (or

"red bag" in lay terms) is an obstetrical emergency.

- This

can be recognized by the appearance of a red, velvety membrane at the

vulva before delivery of the foal.

- The chorio-allantois must be ruptured

immediately and delivery assisted because the foal will rapidly become

hypoxic and anoxic.

- Clients should be made aware of this condition

because if they do not take action and await the arrival of a

veterinarian, the foal will die of anoxia.

- Premature placental

separation is associated with placentitis (the placenta is too thick to

rupture at the cervical star area), twinning, inappropriate induction

methods (PGF) and unknown causes.

- In many cases, the mare doesn't strain

and the premature separation and failure to rupture interferes with

delivery.

- The foal progressively becomes hypoxic, weak, and dead.

- This

condition should be treated as an emergency with rupture of the membrane

and delivery of the foal.

In any case, correction of dystocia should aim to

minimize trauma to the mare.

- Elevation of

the hindquarters with the mare under general anesthesia provides

additional room to manipulate the fetus.

- Fetotomy is a viable solution,

provided trained personnel and proper instruments are available.

Otherwise, trauma to the mare is likely.

- Caesarian section is an

excellent alternative if facilities and personnel are available.

- One of

the biggest problems with fetotomy or caesarian section is the delay in

making the decision to go forward with either option.

- If the decision is

delayed, the mare becomes exhausted and the reproductive tract

traumatized.

- The procedure and recovery then becomes more difficult.

- The

benefit of timely decision making is shown by studies examining elective

c-section in mares in which live foals were delivered, some mares had

repeat sections in following years, others had vaginal delivery and so

forth.

Induction of

parturition

- Induction of

parturition in mares had a bad reputation for years because of inability

to determine when the foal was mature enough for life outside the womb.

-

Induction of parturition based on gestation length alone or even with

the additional information of udder development and relaxation of the

ligaments and cervix resulted in the delivery of premature foals that

needed intensive care to survive and frequently died in spite of the

care.

- With the knowledge of the changes in mammary secretion

electrolytes, however, induction can now be performed safely.

- The

criteria to be met before induction include

- 330 d gestation minimum,

-

colostrum in the udder,

- relaxation of the ligaments and cervix and most

importantly,

- changes in the mammary secretions of >400 ppm (10 mmol)

calcium. This is the KEY CRITERIA.

- Inversion of the Na:K ratio is also

critical (K should be > Na in mammary secretions)

Methods of induction

- It

is advisable to place a jugular catheter before inducing parturition.

Oxytocin is the drug of choice.

-

The dose used is related to the intensity of parturition and the time to

delivery.

-

The smoothest induction is with a low dose (5-10 IU bolus IV

or 10 IU in 200 ml over 15 min).

-

The hypothesis is that a small dose

begins the cascade and the endogenous response carries it on.

-

Other

reported protocols include: single IM bolus (100 IU; 40-60 IU); multiple

small IV injections (10-20 IU) every 10 min; IV boluses (20-40 IU) in 60

ml saline every 20 min; IV drip (60-80 IU) in 500 ml saline; but

parturition is more rapid and forceful with these higher doses.

-

The

trend is toward smaller doses which seem more physiologic.

PGF2a is effective in inducing parturition but

results in an increase in premature placental separation, dystocia and

foal mortality. It is NOT recommended

Indications are that if criteria for induction are

met (including Ca level of mammary secretions), fluprostenol is safe and

effective but the time interval from treatment to parturition is longer

and more variable than oxytocin.

Steroids given repeatedly in high doses will

shorten gestation length but are ineffective for inducing parturition

for practical purposes.

Postpartum

disorders Retained

placenta

- Retained placenta is rare due to

the strong uterine contractions and microcotyledonary attachment of the

placenta in mares.

- Retention usually occurs in the non-gravid horn.

-

Unlike the cow, this should be treated as an emergency.

- Tissue breakdown

and bacterial growth may lead to metritis - laminitis - septicemia

complex.

- The placenta should be passed in 3 h, if not, initiate

treatment prior to 4 -6 h postpartum.

- The aims of treatment are to

stimulate release of the placenta, evacuate the uterus, encourage

involution, control bacterial growth and prevent laminitis.

-

Treatment

- Attempts to remove the placenta manually risk hemorrhage and

trauma to the uterus. Manual removal is not recommended.

- Prior to 4 - 6 h after

parturition

- Re-distension of chorio-allantois may be attempted (Burn's

technique)

- This

method is usually quite effective if there is only a single hole in the

placenta at the cervical star area.

- Insert tube into placenta

(not around it!) and distend with fluid (home

made isotonic saline is good)

- Distend placenta (stand

back when the fluid rushes out)

- Repeat until placenta

releases

- The more effective

oxytocin method is to administer the oxytocin in

an IV drip (50 IU) in 500 ml saline over a 30 min period (this is the '5

method'...... 50 units, 500 mL, 0.5 hours)

- Other methods

include a large IM bolus of 80-100 IU or small IV doses (10-20 IU)

repeated every 15 min.

- Always examine the placenta after passage to make

sure it is all present.

- It

is helpful to know the normal appearance to be able to identify

pathology.

- After 4 - 6 h

- Treatment should

include broad spectrum systemic antibiotics, e.g. potassium penicillin

(22,000 - 44,000 IU/kg, IV, QID) plus gentamicin (6.6 mg/kg, IV, SID)

plus metronidazole (15 mg/kg, PO, BID).

- In addition, uterine lavage with

saline will reduce the accumulation of debris in the uterus.

- The

retention should be manually re-evaluated, at least daily.

- Exercise is

helpful, provided there are no signs of laminitis.

- Make sure that

tetanus vaccination is current. If not, administer tetanus toxoid.

- Monitor the mare for signs of metritis - laminitis - septicemia complex.

Metritis - laminitis - septicemia

complex.

- This problem may develop due to

gross contamination at foaling or retained placenta.

- Affected mares

exhibit depression, anorexia, congested mucous membranes, elevated

temperature, pulse, and respiration rate.

- Signs appear as early as 12 h

postpartum.

- Treatment consists of evacuating the uterus by large volume

lavage (with saline) to eliminate debris and toxins.

- Systemic therapy

consists of systemic antibiotics, fluids, anti-inflammatories, tetanus

toxoid, monitoring for laminitis, etc. as outlined previously for

retained placenta.

Delayed uterine involution

- Normally,

involution in the mare is very fast.

- By 7 d postpartum the uterus is 2 -

3 times the size of the uterus of a barren mare.

- Mares with delayed

uterine involution may have a discharge, occasionally exhibit dullness

or mild pain and on rectal exam have a large, baggy, flaccid uterus.

-

Ultrasound exam reveals excessive fluid in the uterus.

- Treatment

consists of uterine lavage, oxytocin (50-100 U in 500 ml IV drip, or

multiple small doses), exercise (provided there are no signs of

laminitis), antibiotics, etc. Oxytocin therapy is especially important

in cases where the foal is dead because then the normal endogenous

release of oxytocin in response to suckling is absent.

Postpartum hemorrhage

- Hemorrhage

can occur into the broad ligament dissecting between the myometrium and

serosa.

- Clinical signs are characterized by a slow onset (12-48 h), with

signs of colic, sweating, pale mucous membranes and elevated pulse.

-

There may be no signs but a hematoma is found on the prebreeding exam.

-

Diagnosis is by rectal exam and ultrasonography, aided by

abdominocentesis.

- Treatment is basically supportive care and consists of

keeping the mare quiet and providing analgesics.

Uterine prolapse

- This

is a true emergency in the mare.

- Even with rapid attention, the

prognosis for survival is estimated as 50%.

- The uterus should be cleaned

and replaced as soon as possible.

- The vulva is not sutured as in the

cow.

- Treat the mare for shock if needed.

- Administer anti-inflammatories,

systemic antibiotics, tetanus toxoid, oxytocin.

Uterine tears

- The

most common location is dorsal, just anterior to the cervix.

- Initial

treatment is for hemorrhagic shock.

- Surgical repair is indicated, unless

the tear is small and dorsally located.

- They often lead to peritonitis.

-

Medical treatment consists of oxytocin (e.g. 20 IU every 2 h) and / or

ergonovine 1-3 mg i.m., repeated every 2-4 h., along with antibiotics,

and NSAID's.

- Massage per rectum after surgical repair is indicated to

prevent adhesion formation.

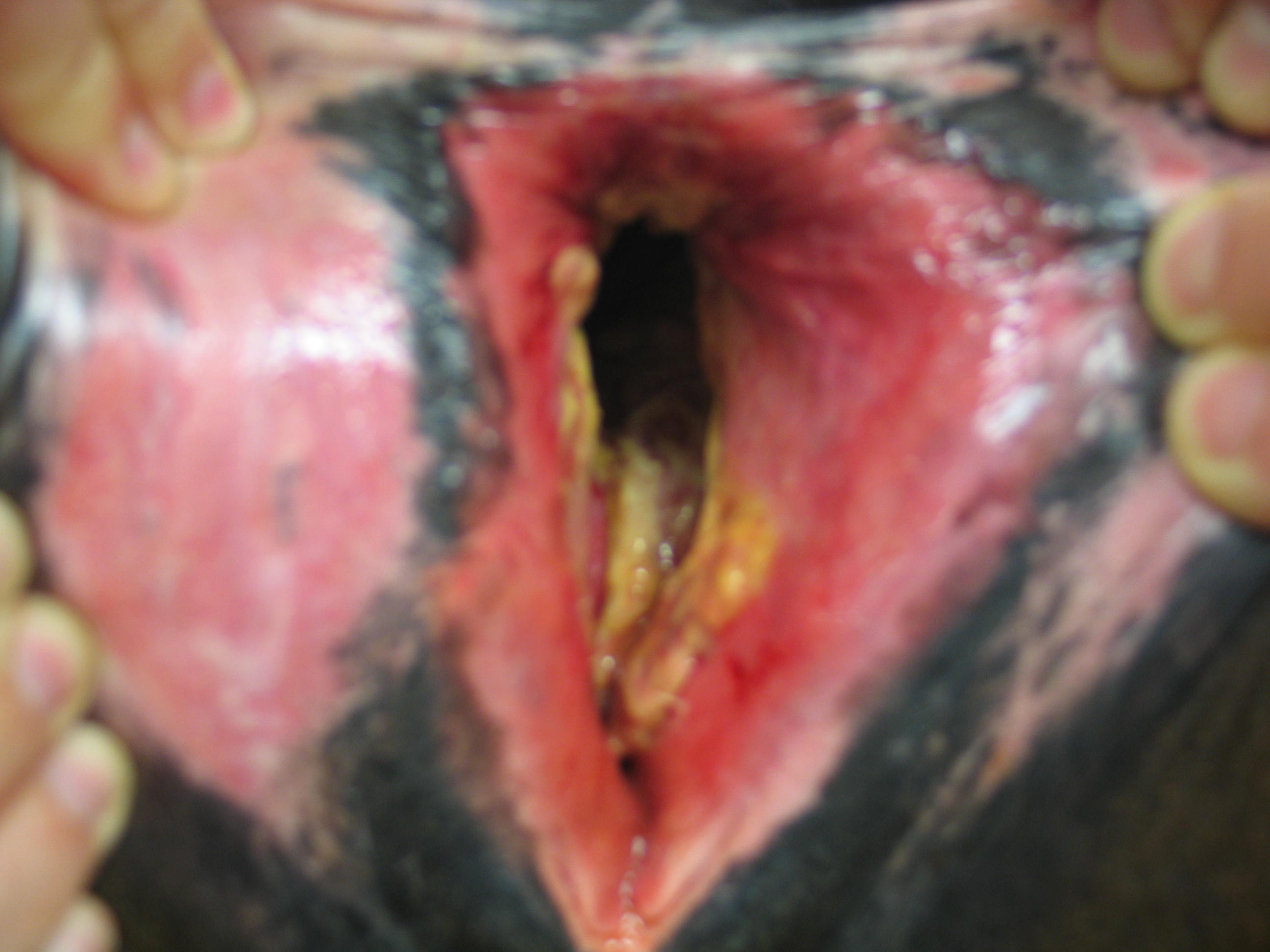

Recto-vestibular and perineal lacerations

-

These are more common in maiden mares due to a tight

vaginal-vestibular sphincter.

-

They also occur in cases of fetal

malpositioning, relative fetal oversize and overzealous assistance.

-

These will be covered more thoroughly in the surgery sessions.

-

Basically, immediate repair can be attempted but if not done immediately

after occurrence, repair should be delayed until the initial

inflammation has subsided.

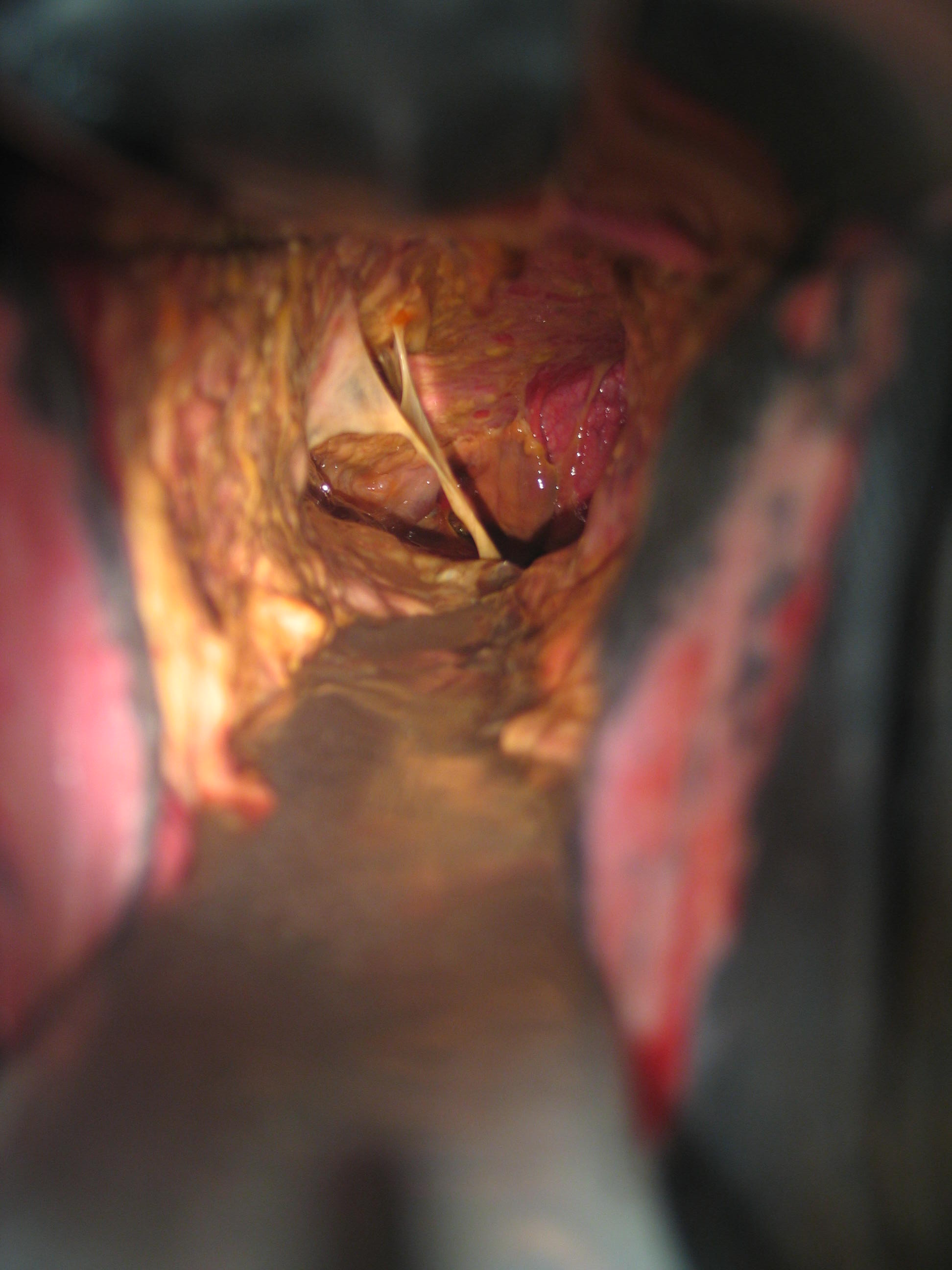

Cervical laceration

- Trauma

to the cervix may interfere with its normal valve like action, affecting

its competency to permit breeding and maintain pregnancy.

- Damage is

often iatrogenic following dystocia or fetotomy.

- Treatment is surgical

repair bur because the surgery is difficult and often unsuccessful, a

BSE is recommended before surgery.

- Cervicitis / Vaginitis

- Necrotic vaginitis and/or cervicitis possible

after dystocia

- Can interfere with urination, defecation

(swelling, abscess formation)

- Treat with antibiotics, NSAIDs, Tetanus

toxoid

Gastrointestinal complications

-

Various complications can occur, including

constipation, small colon bruising, and rupture of the rectum, cecum, or

small colon.

-

Signs of colic and peritonitis follow.

-

The diagnosis can

often be confirmed with paracentesis.

Elective

termination of pregnancy

- Numerous

indications exist, with twinning and inadvertent breeding being some of

the most common.

- The choice of method depends greatly on the stage of

gestation.

- Before 5-7 d post ovulation there is no effective method. The

embryo has not entered the uterus yet and the CL is not responsive to

PGF.

- From 5 d post ovulation until the endometrial cups form at about 35

d, any number of methods will terminate pregnancy.

- Probably the simplest

is an injection of PGF.

- Uterine lavage or manual crushing will also end

the pregnancy.

- In the case of twins, where it is desired to maintain one

vesicle while destroying the other, isolation of one vesicle and manual

crushing is the preferred method.

- Because of the mobility of the early

vesicles, isolation and crushing is best performed before d 16.

- After

the endometrial cups have formed, PGF can still be used to terminate

pregnancy but multiple injections may be necessary.

- Uterine lavage or

uterine infusion can also be used, as well as manual crushing if it is

early enough to be able to grasp the vesicle.

- Various methods have been

employed to terminate one of a set of twins while allowing the other to

continue to term.

-

Currently one of the most promising is ultrasound

guided aspiration.

-

Although only about a third of mares treated with

this technique will carry the remaining foal to term, this is a much

higher percentage than would be successful if no intervention was

practiced.

-

Fetal

decapitation

at

about

75

days

is

the

best

method

to

terminate

twins.

-

Twin Reduction by Cervical Dislocation (as told by Karen Wolfsdorf)

-

Best time to perform surgery is between 75 to 85 days

-

Ultrasound to locate and identify fetuses, choose the one with the least surface area or closest to the tip of the horn

-

Give Banamine pre-op

-

Give 0.5 cc detomidine

-

Clip and give local block

-

Give another 0.5 cc detomidine

-

Give 1.0 cc propantheline (This is critical – if skip this, uterus will be too turgid to be able to perform task - available from HGD Pharmacy)

-

Grid incision (big enough to permit arm in abdomen)

-

Locate fetus, dislocate cervix by rolling between thumb and second finger (bigger fetuses – sort of like popping a cork on a bottle)

-

Routine closure

-

Post-Op Banamine q 12 h for 2 d

-

Double dose Regumate for 30 d

-

Pen/Gent for 3 d, then 7 more d of SMZ

|

Equine

Index

Equine

Index